Eva writes*

In June 2019, the Dutch government set the goal of having as much of a circular agricultural system as possible by 2030. European Union regulations state that objectives of organic agriculture include that distribution channels should be kept short, and that one should aim for a local approach. This means that closing the agricultural cycle should happen at the most local level possible [pdf]. With the current division of agricultural practices in the Netherlands, however, that will be a challenge.

To take an example, farmers in the region of West Zeeuws-Vlaanderen lack local supplies of manure. Therefore, a gap in the nutrient cycle appears: the rate of nutrients taken from the soil is higher than the rate of nutrients returned to this soil. Currently, farmers in the region close the gap with chemical fertilizers and manure imported from Noord-Brabant.

Because chemical fertilizers harm the environment, organic farmers try to minimize the use of chemical fertilizers, meaning greater imports of manure from Brabant. However, the cattle farmers in Brabant often import their cattle feed from far away (Africa, Asia, and the Americas). How sustainable is this organic farming?

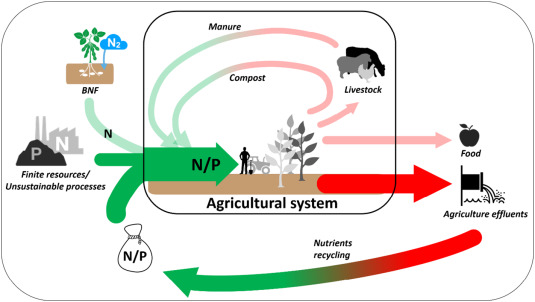

This example shows why it is so important to close the local cycle when we want organic agriculture to actually be a more sustainable option. The issue is that, with current practices, an unclosed local nutrient cycle is unavoidable. That is because of one consistent factor taking nutrients out of the cycle: human consumption. By consuming, we take nutrients out of the cycle, which end up in by-products: food waste, by-products of food processing and, well, our fecal matter. These nutrients are never returned to the soil, which is why manure needs to be imported to fill the gap. However, importing means that there will always be a gap somewhere in the world. Local solutions are needed!

The first steps towards a minimized gap in the local cycle should be the prevention of food waste. This still does not completely close the cycle: full recycling of all by-products is needed, including human excreta. Currently, human fecal matter is still seen as something we would rather dispose of. Nevertheless, seeing that a fully organic agricultural system with locally closed cycles is the goal for 2030, its recycling might be unavoidable. Other options include using legumes for nitrogen fixation. Nitrogen, however, is the only main nutrient that is present in the atmosphere: a fixation process cannot be applied for other main nutrients, like phosphorus and potassium. Therefore, it might become very difficult to find alternatives for all nutrients.

That is why it will probably be beneficial to consider the option of using human fecal matter. Current research shows that there are still some issues with emissions during storage and after spreading, and that human excreta contain contaminants of concern that need to be filtered out first: the development of a proper management system and additional research is clearly necessary. With the ‘local approach’ goal and the unavoidable gap caused by human consumption in mind, however, I would argue that investment in this research is definitely worth it.

Bottom line: By not recycling all by-products of human consumption, there will always be an unavoidable gap in the nutrient cycle. With organic farming being focused on a local circular approach, a way must be found to close this gap locally. Of the many possible strategies, the most obvious one is using our poop!

* Please help my Environmental Economics students by commenting on unclear analysis, alternative perspectives, better data sources, or maybe just saying something nice :).