NB: I started a draft of this post in early 2020. Then COVID happened. I still think there are some interesting ideas in here, but it’s still a bit speculative in terms of identifying, and then connecting, dots. I’d appreciate any comments on this topic, whether or not I’ve addressed them.

This new decade arrived sooner than I expected. I don’t remember the arrival of 2010, but 2000 got a lot of attention. At a risk of over-simplifying, I think people were ready to party in 2000, whereas 2010 arrived in the middle of the Great Recession and 2020 dropped in the middle of a dozen crises, whether fuelled by Trump, other “leaders” (France, India, Iran, Iraq, and Hong Kong) or Nature (climate-fuelled fires, floods, you-name-it).

In this post, I begin with the zeitgeist on a troubled decade, reflect on the forces pushing us back, and end with some ideas for thriving (or self-defense) in the 2020s.

Zeitgeist of the 2010s

- “In the 2010s, it has often felt as if everything is up for grabs – from the future of capitalism to the future of the planet – and yet nothing has been decided. Between the decade’s sense of stasis and sense of possibility, an enormous tension has built up. It is still awaiting release.” — The Guardian (“The age of perpetual crisis: how the 2010s disrupted everything but resolved nothing“)

- “Since 2017, the United States has not only abdicated its role as a stabilizing leader on the global stage, but is also sowing unpredictability and chaos abroad.” — The New York Times (“The 2010s Were the End of Normal“)

- “The public only really unifies around what it rejects. This has profound political consequences. People can’t organize around a common idea or worldview, but they all seem to agree that they’re pissed off and they’re against … the system.” — VOX (“A decade of revolt“)

The pushing-falling-tipping-backwards Counterreformation

We’ve gone into reverse politically (hysterics from Trump, BoJo, Bolsinaro, et al.), socially (as Zuckbot et al. convert friendships into cashflow*), economically (Bezos/Amazon being only one example of crushing monopolies), and environmentally (from climate chaos to over-fishing and logging forests).

* Read this interesting explanation/defense of FB by the guy running its advertising program in the 2016 election. He correctly says that most of the election was won/lost on people’s tribal beliefs, but also calls on FB to be more transparent. [Since I read this article, I’ve read others that are much more critical of FB’s conduct, this one, for example.]

While on holiday in Italy (Jan 2020), we ate dinner with some Americans. One was serving in the Army (base police in Spain, not in combat). “How’s it’s going with Trump?” I asked. “Good for me, I got a raise.” This response really annoyed me, as the raise probably had nothing to do with Trump while Trump’s crazy rhetoric and violent acts are making the US weaker and conflict more likely.

Young people are reading less and “feeling” more, meaning that rationality is replaced by passion, leaders are replaced by populists, and real, hard choices are replaced by fantastic lies. The use of “cancel culture” by both Republicans and Democrats has turned politics into a test of tribal loyalty towards memes and hashtags rather than a process in which the best policies emerge from contested debates. (This entire process can be traced back to Newt Gingrich’s 1994 “take no prisoners” strategy. Leave it to a professor to go for the radical, blow-up-the-country, strategy.)

‘In her comparative study of fallen empires, Jacobs identifies common early indicators of decline: “cultural xenophobia,” “self-imposed isolation,” and “a shift from faith in logos, reason, with its future-oriented spirit … to mythos, meaning conservatism that looks backwards to fundamentalist beliefs for guidance and a worldview.” She warns of the profligate use of plausible denial in American politics, the idea that “a presentable image makes substance immaterial,” allowing political campaigns “to construct new reality.” She finds further evidence of our hardening cultural sclerosis in the rise of the prison-industrial complex, the prioritization of credentials over critical thinking in the educational system, low voter turnout, and the reluctance to develop renewable forms of energy in the face of global ecological collapse.’ — The Atlantic (2016) on her 2004 book, Dark Age Ahead (my 2016 review)

The Four Horsemen of the [Biblical] Apocalypse were pestilence, war, famine and death. Civilization and technology have pushed those horsemen away, but social-media-fueled ignorance and lying populists have brought them back.

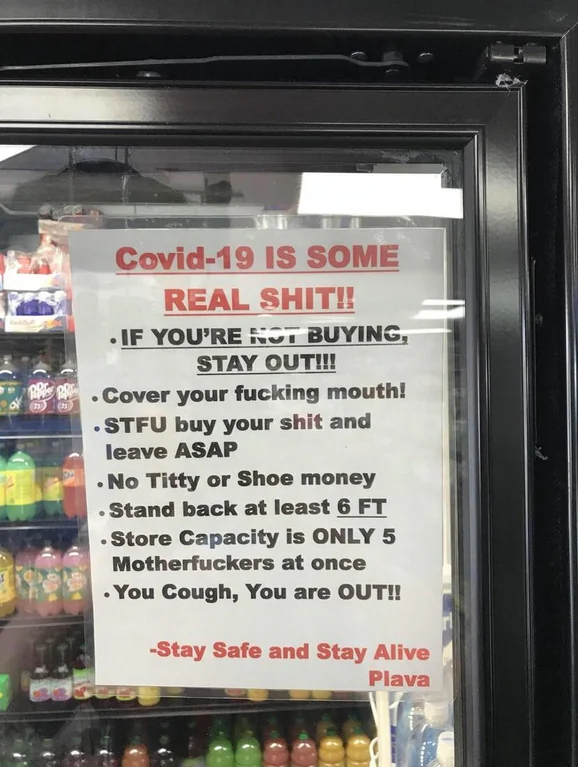

- Pestilence: Climate and political chaos are spreading viruses (e.g., Ebola), super-charging bacteria (e.g., antibiotic-resistent TB), reviving old diseases (smallpox from melting permafrost) and increasing the range of pests (mosquitoes) previously held back by winter cold.

- War is more likely on several dimensions. Technology makes it easier to attack via drones, cyberattacks or small-scale militias. Politicians blame outsiders for their failures, inviting responses that can escalate. Weakening economic ties and progress mean that citizens have less to lose by supporting political aggression.

- Famine has been predicted since Malthus (1798) explored the problem of exponential population growth outrunning linear growth in food supplies. Although population growth is slowing (still on track for 11 billion), our demand for food is driven more by wealth than headcount, which means that food demand (e.g., meat) is rising fast at the same time as water scarcity, topsoil loss, and trade disputes are limiting supplies and increasing the risks of disruptions to essential food trade.

- Death is not negotiable but we’re managed to push back the date of death by decades over the past century, mostly due to improved public health (clean water, vaccinations), but also due to reductions in violence and increases in economic prosperity. All of these forces are weaker or reversing at the moment, under the influences of social media (ignorant anti-vaxxers**), falling spending on infrastructure and public health, and politicians who solve problems with “blood and iron” instead of thoughtful negotiation.

** I wrote this before Covid was a thing. Now we know just how dangerous — to themselves and society — these anti-vaxxers are.

The Guardian thinks the 2010s were a rerun of the 1970s, in the sense of building up an anxiety that fed the radical changes of the 1980s (Thatcher/Reagan revolutions). What kind of revolution will we get this time around? Although “socialist” might seem the answer, I worry that it might start off sounding good but quickly turn into a populist “socialism” that destroys everything around it in an unsustainable quest for purity in the service of the masses, an echo of the Reign of Terror or Red Terror that overthrew “civilisation” (respect for others, rule of law) in Revolutionary France and Russia, respectively.

The Roaring or Whinging 20s?

- Parts of the rich world are now emerging from over a year of COVID-restrictions. Some are “revenge shopping”, others are still paranoid. Few are “back to normal” — whatever that is — due to the ongoing toll of COVID in poor — and poorly governed — countries.

- Climate chaos is also a lot more in our faces, as Why we’re failing to stop climate chaos.

- Trade wars, disrupted supply chains, and geo-political struggles between an assertive China and reactionary America are not making International cooperation and mutually-beneficial economic development any easier.

From where I sit today (a few days after my 52nd birthday), I am more inclined to pick “whinge” (blaming others) over “roar” (we’re all amazing!), mostly because populists and social media are feeding paranoia via “othering”, because the rich and powerful are grabbing more for themselves, and because climate chaos is destroying our assets (forcing us to spend more of our income on “staying in place,” which makes us think we’re relatively poorer).

In a world of a “shrinking pie,” it’s hard to be generous towards others, and it’s doubly hard when those others are from a tribe that’s “out to get you.”

My one-handed advice

- Don’t feed the trolls. Most influencers are attention whores. Ignore them. Spend your time on better people. Evgeny Morozov has some good ideas for escaping bad social media dynamics.

- Do take care of family and friends. You will need them if you’re going to have a foot in the world of sanity — and especially as climate chaos tears our world apart. Have dinners, drinks, and phone calls with 10 (close) or 140 (at best) friends. Don’t doom scroll thru the delusions of your 1,236 “friends” on social media.

- Do make good (moral) choices. You need to live with yourself, and it’s quite common for devious choices to backfire. Live as if karma mattered.

- Do keep your powder dry. Climate and political chaos will make life more expensive, by destroying and reducing your choices, respectively. Save money. Build assets (financial, physical and social). Live simply so you’re not too upset at losses.

- Do count your blessings. We’re richer than any generation of human history. We can drink the water (mostly). We can eat good food. We have abundant ways of spending time without spending money. Get off the hedonic treadmill and breathe.

What about me?

I have a good job teaching, a great relationship, and lots of (scattered friends). I can engage my mind with my students, my peers, and anyone on the internet who listens to my podcast, or reads my writing (blog, books, papers). I put more time into fun “concrete” activities such as my boats (!) and wood-working. I like picking up garbage on the streets (while I do my Dutch lessons 🙂

Critical thinking isn’t easy to begin with, but you can start by opening the other door, cancelling that repeating event, or taking to strangers. Such exercises help you grow, connect with others, and strengthen yourself financially, mentally, physically, and socially.

Good luck! (We’ll all need it.)