Laura writes*

In 2018 Capetonian dams dropped to 26% of their capacity, signalling a crisis. Now the dams are full, but water remains scarce and the city vulnerable to extreme weather events and physical water scarcity. Cape Town, as one of the most unequal cities in the world, is also facing social water scarcity. It is estimated that one million people, almost ¼ of the population, are using only 4.5% of available water.

The City of Cape Town introduced a “stepped tariff” (increased block rate) which provides the first 10,500 L (the first two blocks) of monthly water use for free to indigent households. However informal housing settlements are not connected to the municipal water distribution system. Without a water connection, those residents cannot redeem the free water.

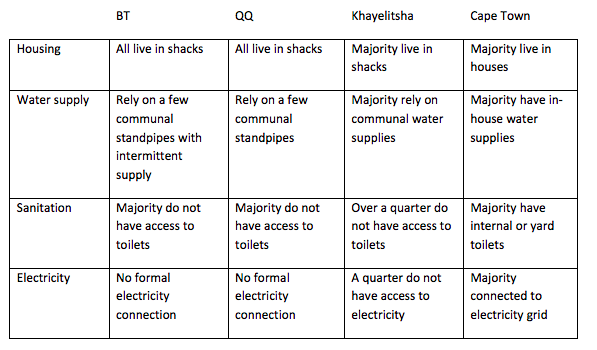

Khayelitsha, Cape Town’s biggest township with a population of more than 2 million [pdf] is facing severe water shortage and inadequate sanitation. Thirty percent of residents live in formal housing (government housing) with in-house water and sanitation facilities, while 70% depend on communal taps and inadequate sanitation. In section QQ (see below), eight standpipes serve 3000 people who, lacking sanitation services, must ask neighbors in formal housing if they can use their toilets. (At night, people have to defecate in buckets they empty into drains in the morning.) Khayelitsha residents face even greater scarcity due to COVID-19 regulations that also make it harder to share facilities. Inadequate sewage disposal also threatens local waterways.

Townships are frequently expanding, often onto private land. The Water Service Developing Plan (WSDP) specifically distinguishes between private and municipality-owned land [pdf], which means that water and sanitation services are not provided on private land. Private landowners do not step in to fill this gap because they do not want to encourage further invasion of their property. The municipality could buy private land, but money is scarce due to subsidised water prices that can only be sustained with outside funding.

Corruption also diverts funds. Instead of providing informal dwellers with appropriate facilities, the local government has built 40,000-unit middle-income houses in a wetland area, thereby reducing aquifer recharge. This “economic growth” worsens water scarcity and social injustice.

Bottom Line: Cape Town’s corruption, bad financial management and negligence of the poor has left ¼ of the city’s population without adequate access to water and sanitation, exacerbating health threats to residents additionally burdened with COVID.

* Please help my Water Scarcity students by commenting on unclear analysis, alternative perspectives, better data sources, or maybe just saying something nice 🙂